César de Pina Station

Inaugurada em 21 de agosto de 1923, inicialmente foi chamada de Chacrinha; mais tarde, recebeu o nome em homenagem ao engenheiro Augusto César de Pina, o primeiro diretor da EFOM. Situada em terras anteriormente pertencentes à família Passarini, imigrantes italianos, a Estação foi importante para o transporte de passageiros, mercadorias, minérios especiais e gado com direção a São João del-Rei. O edifício era composto de um armazém para guardar mercadorias que vinham de trem, uma agência de Correios e uma bilheteria. O trem operava em trilhos com uma bitola de 76 cm e foi desativado em 1966.

Subsequently, the César de Pina Neighborhood developed, known until 1991 as Córrego das Pedras (Stone Creek). Due to its deteriorating condition, the Tiradentes city government, through the City Council for Cultural Policies and Heritage, restored the Station, which reopened in 2023. César de Pina Station was officially designated as a heritage site by city law in 2007.

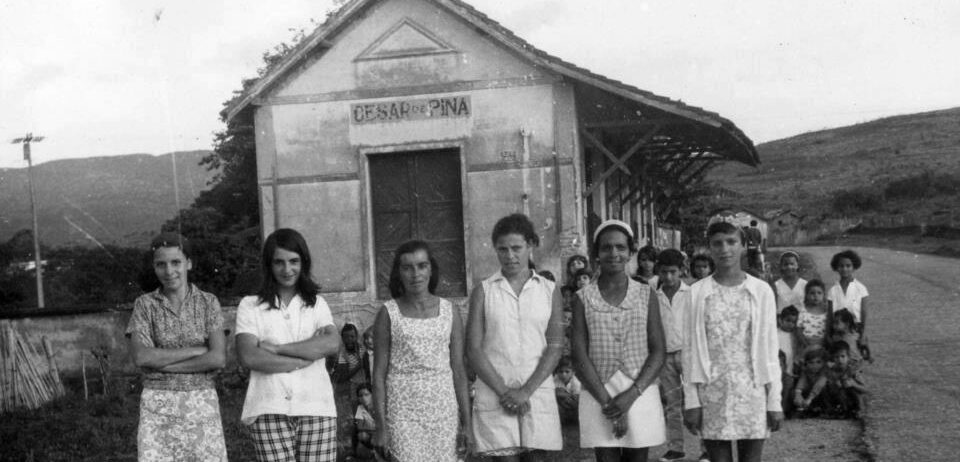

César de Pina Station - a gathering of catechists, children, and staff, including Mr. Ataliba Reis, who served as the station's keeper. Author unknown, 1940s. Maria Aparecida Gomes Pitt Collection.

Warehouse and religious house in the César de Pina neighborhood, 2012.

Luiz Cruz, 2012. Author's collection.

Casa da Cerâmica (Ceramics House) in the César de Pina neighborhood, 2012.

Luiz Cruz, 2012. Author's collection.

César de Pina Station after restoration in 2023.

Marina Fares, 2024. Agência de Iniciativas Cidadãs (AIC) Collection.

The Surroundings of César de Pina Station

A César de Pina era um ponto central para encontros de pessoas que moravam nos atuais bairros de São João del-Rei: Giarola e Colônia do Marçal. Na década de 1960, o imigrante italiano João Domingos Longatti doou um terreno na região da estação para a construção de uma escola, com o objetivo principal de criar um espaço de estudo para seus próprios filhos. A escola atendia somente meninos, com duas salas de aula e alunos de diferentes idades. Nas proximidades, um armazém era utilizado para a comercialização de diferentes produtos, como embutidos, bebidas e doces. Ainda havia uma casa de cerâmica que produzia mercadorias para transporte e comércio no trem. Em frente à Estação, um campo de futebol reunia os moradores, proporcionando partidas de futebol de times da região. Aos domingos, a Estação tornava-se ponto de encontro e diversão dos moradores. Atualmente, no entorno da estação existem apenas as ruínas de uma casa religiosa e do armazém.

Italian Immigration

The influx of Europeans to Brazil was encouraged by the Portuguese government during the reign of Dom João VI (1816-1822). This migratory movement gained momentum with the end of the slave trade in 1850 and the abolition of slavery in 1888. The demand for labor and the political project to 'whiten' the Brazilian population spurred the arrival of European workers. Italian immigration to Brazil peaked between the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Italian immigrants initially found opportunities in agriculture and settled in the south and southeast of Brazil, where they formed colonies. In São João del-Rei and Tiradentes, Italian families such as the Giarolas, Longattis, Passarellis, Lovattos, and others came in search of a better life in Brazil. Land donations primarily took place in what are now the Colônia do Marçal neighborhood of São João del-Rei and the César de Pina neighborhood of Tiradentes.

Ships carrying Italians arriving at the port of Santos, São Paulo. Author unknown, 1907.

Immigrant registration documenting Longatti's arrival in Brazil through the São Paulo port at the end of the 19th century. Public Archives of the State of São Paulo Collection, 19th century document.

Longatti’s Fruits

In Tiradentes, Italian immigrants initiated the cultivation of foods previously unfamiliar to the region. The production of vegetables and fruits such as tangerines, oranges, plums, apples, pears, lemons, and other citrus fruits began to flourish in the area around César de Pina Station. Tangerines became well-known for their production and marketing, largely thanks to the efforts of the Longatti family. The person responsible for the production was João Domingos Longatti, known for transporting and selling his products in his truck, in the city of São João del-Rei and in the vicinity of César de Pina and Águas Santas Stations. César de Pina Station served a vital role in linking the local community and its productions with São João del-Rei.

Longatti family selling tangerines at the Feast of the Holy Trinity.

Author unknown, 1967. Image from Paulo Gil Soares' film “As proezas de Satanás na Vila do Leva e Traz.”

“Italy was overcrowded, leading to many being sent on ships as immigrants. The sea voyage to Brazil lasted three months, during which even women worked tirelessly. They were provisioned with enough food for three months.”

Ivone da Conceição Longatti, resident of the Colônia do Giarola neighborhood in São João del-Rei.

“This place was really all about farming, you know? Everything we grew, like corn, beans, greens, and all sorts of veggies, we loaded onto the train for São João del-Rei. Italian families, particularly the Longattis, were deeply involved in this. They put so much into farming that they're still at it, even now. A few of them are still out there, working the land.”

Luiz Antonio da Cruz, teacher, researcher and resident of Tiradentes.

“Italian immigrants arrived in São João del-Rei in the last century, and much of the early development there was closely intertwined with this new influx. Initially, their focus was primarily on agriculture. Later, they diversified into various other activities and dispersed across the region. Today, Italian communities can be found in several places, with many residing in Santa Cruz de Minas. A railway branch extended to this area as well.”

Luiz Antonio da Cruz, teacher, researcher and resident of Tiradentes.

“The colony of Italians supplied São João because Italian culture was more advanced, with a tradition in the cultivation of fruits and vegetables. In 1888, approximately a hundred Italian immigrant families arrived in the region of Tiradentes and São João del-Rei.”

Father Ademir Sebastião Longatti.

“I used to make strings of tangerines and take one for myself. I'd take a wooden stump, like this, about the thickness of a caliber, and tie a strong string underneath it. One person would hold it, spinning it; the other would hold the string and attach tangerines to it; we’d spin and attach, and that string of tangerines would grow. It looked beautiful. Then, I'd sell those strings to people strolling here on Avenida in São João on Sunday mornings. So we carried tangerines in the bornal—there weren't bags like that, it was a bornal.”

Father Ademir Sebastião Longatti.

“When the Italians came, they brought along new produce. We weren't familiar with tomatoes, beets, carrots... we were acquainted with pumpkins and kale, along with a bit of manioc. But when the Italians arrived, they introduced all these new vegetables and fruits—they brought plums, tangerines, a sour, tart little apple, and regular apples as well.”

João Bosco Barbosa, retired, son of the head of São João del-Rei Station.

On the route that linked São João del-Rei to Águas Santas, passing through César de Pina Station, the train consisted of various types of wagons. The station played a crucial role as a trading hub. Alongside the first and second-class passenger cars, there was a designated car for the Post Office, facilitating the distribution and delivery of parcels. Additionally, freight wagons were used for transporting manganese, cattle, and horses.

In addition to freight services, the station served as a departure point for residents traveling by train for various purposes. Young people would take the train to attend school, either near César de Pina or in São João del-Rei. Residents also frequently utilized the train to travel to Águas Santas, where mass was held once a month at Capela Nossa Senhora da Saúde (Our Lady of Health Chapel).

“I started dating my husband here on the train. The train would pass by so he could head to work at Siderúrgica Fluminense (Fluminense Steel Plant), and I would be on my way to my sister's house in the city. He would get off the train to go to the steel plant, and I would continue on to César de Pina. Eventually, my dad noticed how close we were getting and allowed us to date.”

Ivone da Conceição Longatti, resident of the Colônia do Giarola neighborhood in São João del-Rei.

“What stands out to me about César de Pina is the abundance of special ore that filled the wagons. I recall an incident where the heap of ore was away from the wagon, and they attempted to move the wagon forward. However, the wagon was already carrying about twenty thousand kilos. When they released the brake, it started to roll downhill. They couldn't stop it on the curve just below, and it eventually toppled over.”

Father Ademir Sebastião Longatti.

"César de Pina Station served as a meeting point. From here, cattle, corn, rice, and beans produced in the region were transported by train to São João del-Rei, and from there, to other destinations."

Father Ademir Sebastião Longatti.

“Products like rapadura and black sugar, which were made in Coroas—a place close to César de Pina—weren't produced in César de Pina itself. These were novel items; as children, we adored these sweets for their delightful taste. Men particularly enjoyed cachaça, which wasn't produced in César de Pina. It came from Coroas instead.”

Father Ademir Sebastião Longatti.

“On Sundays, everyone would gather and say, 'Let's go for a walk, see the train.' Everyone would watch the train arrive, and always in good company. In front of the station was a football field, a beautiful sight, always bustling with people.”

Ivone da Conceição Longatti, resident of the Colônia do Giarola neighborhood in São João del-Rei.

“Tem uma história pitoresca que eu estou lembrando que o vovô me falava. Isso aí foi em 1912, 1915, no máximo. O vovô falava que, em dia de domingo, a gente ia pra Estação, porque dia de domingo na parte da tarde era livre, na parte da manhã tinha que trabalhar. Na parte da tarde meu bisavô dava folga. Não estou falando da minha família só não. Os outros também eram assim. Na folga, o vovô adorava ir para Estação à tarde: ‘Ah, mas por quê, vovô?’ Ele olhava para ver se não tinha ninguém e falava: ‘Pra ver a canela das mulheres’”.

Father Ademir Sebastião Longatti.

"It was a regular stop. At these stops, the station was always immaculate, the tracks meticulously swept. We'd sit on the platform, where there was a radio—a radio station, you know? It belonged to the head of station’s house, but he'd set up the sound for us, and we would listen."

João Bosco Barbosa, retired, son of the head of São João del-Rei Station.

Freight Transportation at César de Pina Station

On the route that linked São João del-Rei to Águas Santas, passing through César de Pina Station, the train consisted of various types of wagons. The station played a crucial role as a trading hub. Alongside the first and second-class passenger cars, there was a designated car for the Post Office, facilitating the distribution and delivery of parcels. Additionally, freight wagons were used for transporting manganese, cattle, and horses.

In addition to freight services, the station served as a departure point for residents traveling by train for various purposes. Young people would take the train to attend school, either near César de Pina or in São João del-Rei. Residents also frequently utilized the train to travel to Águas Santas, where mass was held once a month at Capela Nossa Senhora da Saúde (Our Lady of Health Chapel).