LOCOMOTIVE IN THE SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI PLATFORM

Ron Ziel, 1970's. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 37 IN THE TURNTABLE

Ron Ziel, 1970's. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 39 IN THE SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI PLATFORM

Ron Ziel, 1970's. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVES IN THE ROUNDHOUSE

Ron Ziel, 1970's. Welber Santos's personal collection.

EXIT TO THE AVENIDA LEITE DE CASTRO

Herbert Graf, 1979. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 42 IN FRONT OF THE ROUNDHOUSE

Herbert Graf, 1979. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE IN THE WORKSHOP

Herbert Graf, 1979. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

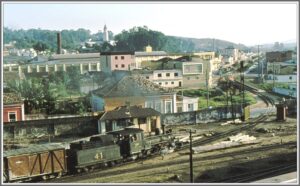

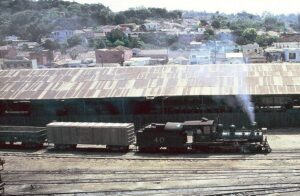

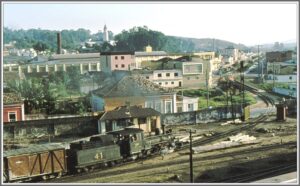

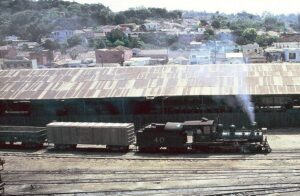

SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI'S RAILWAY YARD

Herbert Graf, 1979. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 120

Ramiro Nascimento, 1981. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

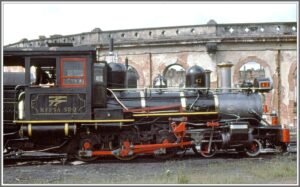

LOCOMOTIVE 37

Herbert Graf, 1979. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

AVENIDA LEITE DE CASTRO

Ramiro Nascimento, 1981. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

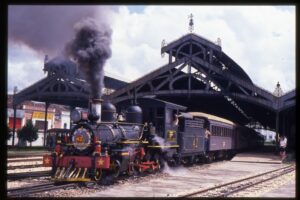

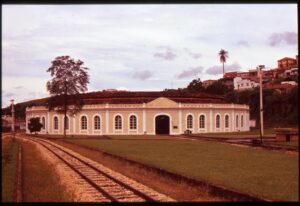

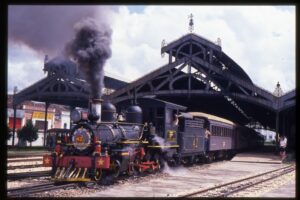

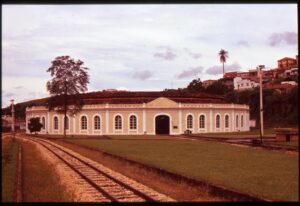

SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI STATION

Ramiro Nascimento, 1981. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

Railwaymen’s Square

Ramiro Nascimento, 1981. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 42 AND 60 IN THE YARD

Mario Arruda, 1983. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

EXIT OF THE RAILWAY COMPLEX

Mario Arruda, 1983. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

WAGON IN THE YARD

Mario Arruda, 1983. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 21

Mario Arruda, july of 1982. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 58 NEXT TO THE WORKSHOPS

Jim Livesey, 1976. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 62 IN THE PLATFORM

Jim Livesey, 1976. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 69 AT THE TURNTABLE

Jim Livesey, 1976. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE NEAR THE RIVER

Jim Livesey, 1976. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

WAGONS IN THE PLATAFORM

Guido Motta, 1974. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 21 IN THE PLATFORM

Christopher Beyer, 1989. Welber Santos's personal collection.

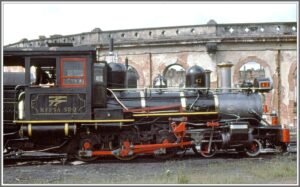

LOCOMOTIVE 42

Christopher Beyer, 1989. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 37 IN THE RAILROAD YARD

Walter Serralheiro, 1978. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 38 IN BARROSO

James Waite, september 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

WAGON INSIDE THE ROUNDHOUSE

Christopher Beyer, 1989. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 40 NEAR THE WORKSHOPS

Ramiro Nascimento, 1981. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

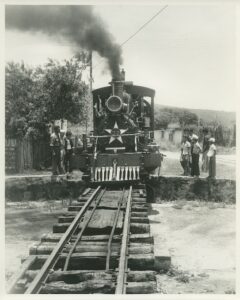

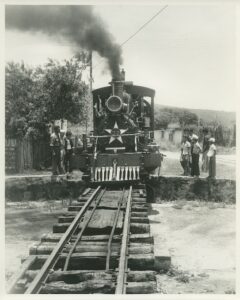

RAILWAY WORKERS WITH LOCOMOTIVE 41

Guido Motta, 1972. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVES 41 AND 66

Guido Motta, 1974. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 42 AT ROUNDHOUSE DOOR

James Waite, september 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

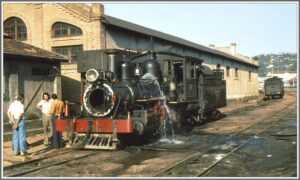

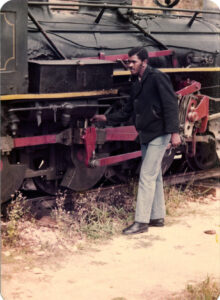

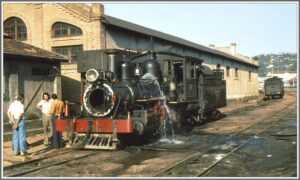

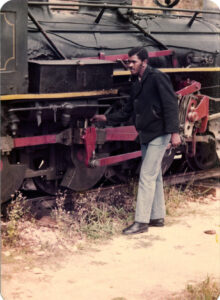

MAN NEAR A LOCOMOTIVE

Walter Serralheiro, 1978. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 43 FUELING IN THE WATER TANK

Walter Serralheiro, 1978. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE IN THE RAILS

Walter Serralheiro, 1978. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

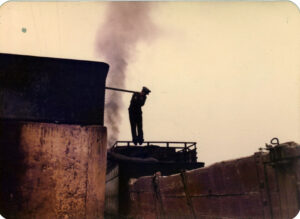

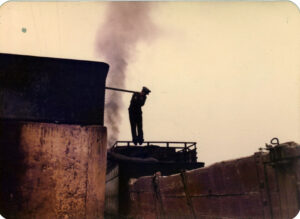

RAILWAY WORKER FUELING A LOCOMOTIVE

Walter Serralheiro, 1978. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

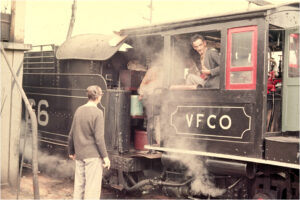

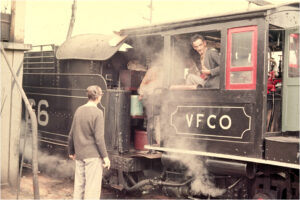

RAILWAY WORKERS AND LOCOMOTIVE NUMBER 66

Guido Motta, 1974. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 66 BY THE WATER TANK

Guido Motta, 1974. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE AT NIGHT

James Waite, september 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE IN THE TURNTABLE

James Waite, september 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 40 IN THE ANTÔNIO CARLOS STATION

Rainhard Gumbert, unknown date. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE IN COQUEIROS STATION

Rainhard Gumbert, unknown date. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 62 IN IBITURUA STATION

Rainhard Gumbert, unknown date. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVES IN IBITURUNA STATION

Rainhard Gumbert, unknown date. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 55 IN AVENIDA LEITE DE CASTRO

Jim Livesey, 1976. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVES IN AURELIANO MOURÃO STATION

Rainhard Gumbert, unknown date. Welber Santos's personal collection.

ROUNDHOUSE

Christopher Beyer, 1989. Welber Santos's personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 21 IN THE PLATFORM

James Waite, september 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

RAILWAY WORK IN THE TRACKS

Christopher Beyer, 1989. Welber Santos's personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKER WITH LOCOMOTIVE NUMBER 55

Jeffrey Stebbins, 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS AND LOCOMOTIVE 55

Jeffrey Stebbins, 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 55 IN THE WATER TANK

Jeffrey Stebbins, 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 55 RELEASING STEAM

Jeffrey Stebbins, 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.

LOCOMOTIVE 55 PARKED IN THE STATION

Jeffrey Stebbins, 1977. Welber Santos’s personal collection.