Train lovers

The importance of the steam train – or "Maria-Fumaça," as it is more commonly known – for São João del-Rei cannot be overstated. The locomotive holds a special place in the childhood memories of many individuals and families, from those who lived near the railway tracks to those who simply hear the distant whistle echoing across the city. The allure of witnessing the train in action and the chance to connect with history through the railway may help to explain the profound impact it has on the population. To truly grasp why the locomotive remains such a revered symbol of the city and a key part of our national history, one must understand the community's deep-seated interest in preserving the technical expertise and traditions associated with the train.

"When I hear the whistle in the distance, it sends chills down my spine. I instantly feel the urge to catch sight of the locomotive. Even if it passes by the same spot three hundred times, the same machine, the same scenery, I always feel compelled to look. It's as if the whistle were a voice, the air pump its heart, the sound of the engine's motion a stride, and it's almost human."

Recounting by Gustavo Zenquini, assistant industrial mechanic, researcher, and local resident.

"I used to stand there, like those curious kids back then, hardly uttering a word, but the sight of the train left me spellbound. Since I was a child, it's like that quote from Hobsbawm, ‘monstrous and noisy serpent, breathing fire and smoke.’"

Recounting by Bruno Campos, researcher and local resident.

"At times, while I'm in the workshop cleaning the machines, because I'm quite meticulous about them, I take pleasure in seeing them gleaming, just like the old ones. It's something I insist on! Whenever I'm operating them, my machines must be spotless, you know?"

Recounting by Alexandre Campos, traction inspector and train driver

"Wow, I used to regard the locomotive as if it were the Comet Halley. So, the vivid memory I have is of finding it to be truly magnificent. How is it possible for something like that to move and function?"

Recounting by Francisco Marques, retired mechanic supervisor

"My family relocated here in March 1970, and we settled on Avenida Tiradentes, behind the Railway Station. One of the most memorable aspects for me was the steam train. Every morning, bright and early, around five o'clock, it would whistle – a loud, sustained sound. It marked the first departure of the day, but it would whistle several times throughout, without fail, from Monday to Friday, and even on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. Whether it was departing or arriving, I, as a teenager back then, was always deeply moved. Even now, the sound of the train whistle stirs something within me. I currently live on a street facing the Roundhouse, and whenever I hear the steam train’s whistle, I rush to the window to catch a glimpse of it passing by: My granddaughters and I, actually, whenever they're visiting."

Recounting by Maria Marcia Silva, retired public servant and local resident.

"Railway workers take immense pride in their tireless dedication to the job. It's truly remarkable. Whether in factories or on the railway, the feeling remains the same. It's a generational tradition, with sons following in their fathers', grandfathers', and even great-grandfathers' footsteps. There's an emotional bond with the machines – locomotives become almost like family members, cherished by engineers."

Recounting by Paulo Lima, sociologist and local resident.

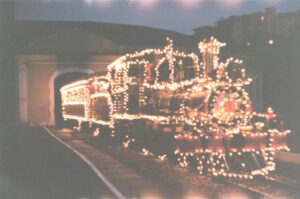

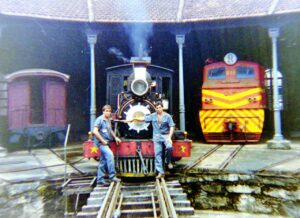

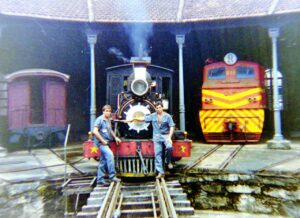

LOCOMOTIVE 21 AT ROUNDHOUSE DOOR

Author unknown, date unknown. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

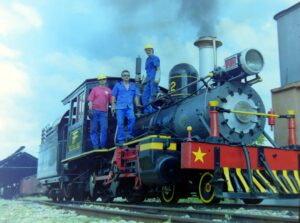

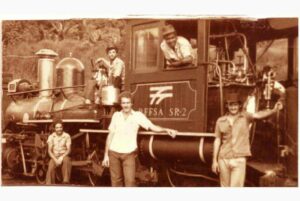

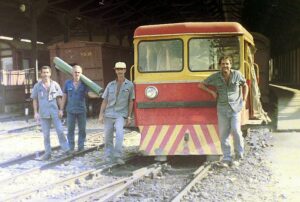

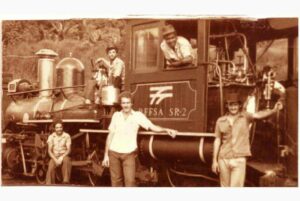

EULER, EDMAR VIANA AND MARIO BRAGA WITH LOCOMOTIVE 22

Hugo Caramuru, 1996. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

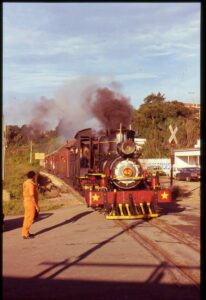

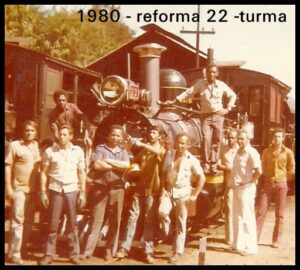

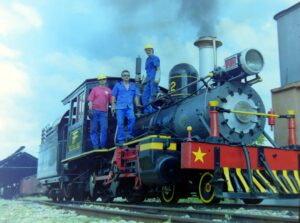

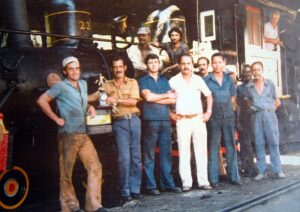

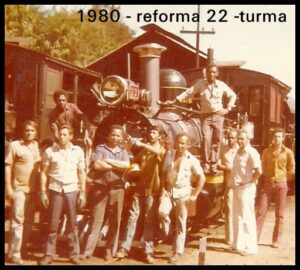

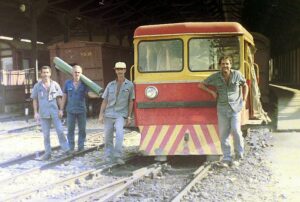

RAILWAY WORKERS WITH LOCOMOTIVE 41 IN BARROSO

Gentil RFFSA, 1980. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

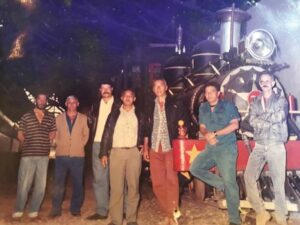

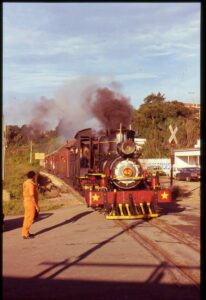

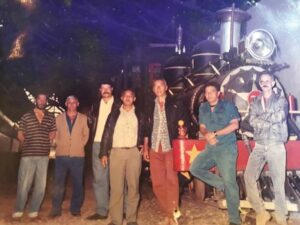

LOCOMOTIVE 42 GOING TO COURTYARD ENTRANCE

hristopher Beyer, 1989. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

Hard and Hazardous Work

Railway work is a complex process filled with challenges and setbacks. Long working hours, the need for both physical and intellectual strength, as well as environmental factors like rain and drought, and vegetation growing between the tracks, were all part of the daily life of railroad workers. Derailments, operational problems with boilers and machinery, collisions, and inadequate working conditions were common, especially throughout the 20th century. Over time, oversight and safety mechanisms improved. One of the major initiatives toward enhancing worker safety was the formation of Internal Commissions for Accident Prevention in companies, known as CIPAs.

I was six years old when the accident involving the Coke truck happened. It wasn't at the station, it was in Matosinhos. I was at the square waiting for the train. It was around 1980. The train was coming, and the Coke truck got on the track. The train hit and knocked the truck over. People loved it. People got on the train, taking glass bottles of Coke. My grandmother lived nearby. There were wheelbarrows to haul Coca-Cola. It was really cool!

Recounting by Bruno Campos, historian and local resident.

ACCIDENT WITH LOCOMOTIVE 41

Author unknown, 80's. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

Accidents always happened. Flooding in the river or a train stuck in a particular spot was quite common. In some places, the train couldn't reverse. Sometimes you had to go and tow it.

Recounting by Francisco Marques, retired mechanic supervisor

“Deve ter começado a vigorar com as exigências em 1974, 1975. Não havia essa análise de acidente, a pessoa machucava, ia lá no médico, ele dava lá dez dias de atestado, e às vezes o acidente não era para tal. Quando foi implantada a CIPA, começamos a dar palestras, ensinar que a pessoa que mexe com solda tem que usar os óculos, luvas, avental… Foi criando mais regras. Mas, do outro lado, tinha a resistência de quem já estava acostumado a só trabalhar sem equipamentos de proteção. E, com a implantação da CIPA, começou a ser investigado. Se alguém se acidentou, nós temos que saber o porquê. Passamos a ter as noções de condição insegura e ato inseguro. E aí começou a educar as pessoas a tomarem cuidado com a execução do serviço prevalecendo a segurança, até o pessoal se acostumar com isso.”

Recounting by Francisco Marques, retired mechanic supervisor

A TRAIN ACCIDENT DESCRIBED IN AN EX-VOTO

Author unknown, 1915. Original from the Church of Matosinhos, São João del-Rei.

Crew Houses

Between stations, there were clusters of three or four houses every six kilometers or so. Railwaymen who worked on the maintenance of the line and foremen lived there with their families. These railwaymen were responsible for inspecting the tracks and monitoring potential obstructions to train passage.

“Eu digo que sou ferroviário desde que nasci. Meu pai trabalhava na via permanente, ou trabalhador de linha, como falamos e morávamos nas casas de turma. Eu nasci quase em cima de um trole, e criado margeando a ferrovia. Ali eu comecei a trabalhar na rede quando as locomotivas eram a carvão. Sempre que os foguistas iam jogar carvão na fornalha e esse carvão caía para fora, a gente catava porque achava interessante. Nossa mãe usava esse carvão para passar roupa e o resto a gente vendia. Havia algumas pessoas que compravam. Eu fui crescendo às margens da ferrovia e passei a levar almoço para o meu pai, quando ele trabalhava ao longo da linha. Ali a gente morou.”

Recounting by Francisco Marques, retired mechanic supervisor

My father was a railway worker from 1948 until 1971, the year he died. At the time of my birth, he lived in a crew house in Padre Brito. His name was Antônio Barbosa da Silveira, but he was known as Bemden. When trains would pass by, whistling through the crew houses, my father would always say: 'You’re going to be a train driver, you know?' Unfortunately, he didn't live to see it, because he passed away in '71 and I started in '76.

Recounting by Moacir Silveira, retired train driver

CONGO FINO TRACK MAINTENANCE CREW

João Bosco Alves, 1976. João Bosco Alves’s personal collection.

From left to right: Avelino, José de Paula Xisto, José Martins, João Bosco, Nivaldo Zampieri, Antônio Jacinto and Delvair Zampieri

Leisure Activities of Railway Workers

The friendship and camaraderie among railway workers are fundamental for railway work, not only during operational moments when teamwork is essential but also after the end-of-shift siren. It was then that friends, jokes, and partnerships flourished. From soccer teams competing in the Factory Tournament on May 1st to the tranquility of fishing and picnics, from the Carnival block Unidos da Chagas Dória to the Holy Trinity Festival in Tiradentes, these leisure moments extended the relationships among the railway workers beyond working hours.

"It was good to work on the railroad. It was a good job. Good people, you see? It was a fun and joyful job. Colleagues were all cheerful. We traveled with colleagues and so on. I've even worked in Divinópolis and Aureliano Mourão."

Recounting by Sebastião Florêncio, retired train driver

"What I miss most is friendships and friends. There were days when 20, 30 people got to the accommodation, several drivers, both here and in Aureliano Mourão. Everyone had to cook together. There was only one TV set, there were three beds in one room, so you could chat with your colleagues until late."

Recounting by Moacir Silveira, retired train driver

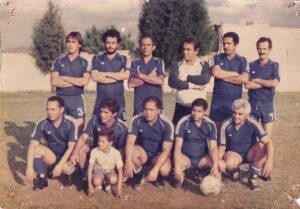

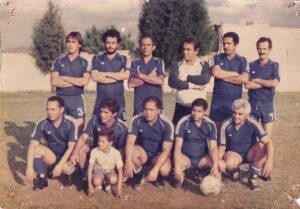

SOCCER TEAM IN THE FACTORY TOURNAMENT

From right to left: Benedito, Moacir, Zé, Carlos Alberto, Tião Fagundes, Paiva, Jaci, an unidentified colleague, Avelino, Nunes and Hugo.

Author unknown, October 23, 1990. Solange Paiva's personal collection.

EASTER – EMPLOYEES AND THEIR FAMILIES

Author unknown, 1964. César Reis’s personal collection.

THANKSGIVING MASS FOR RAILWAY WORKERS

Author unknown, 1960s. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

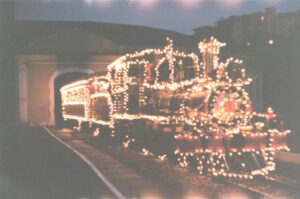

LOCOMOTIVE 43 IN TIRADENTES IN THE HOLY TRINITY FESTIVAL

Author unknown, 1982. NEOM ABPF Collection.

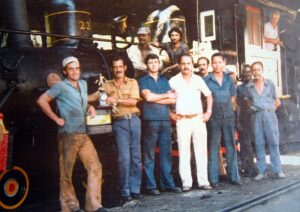

RAILWAY WORKERS IN THE FACTORY TOURNAMENT ON MAY 1ST

Author unknown, 1980s. João Bosco Alves’s personal collection.

Standing up: Toizinho, Zé Anésio, Jilozinho, Heitor, Nivaldo, Ademir, Paulinho and Luiz Carlos.

Crouching down: Nelson, Geraldo Guimarães, João Bosco Alves, Bento, Pantera, João Bosco Fuzate and Dário.

SOCCER TEAM IN THE FACTORY TOURNAMENT

Author unknown, 1980s. Moacir Silveira’s personal collection.

Standing up: Adilson, Cleidimar Clareti, Avelino, Carlos Alberto Pinto, Luiz Henrique Mamão and an unidentified colleague.

Crouching down: Nunes, Gilberto, an unidentified colleague, Clevio, Edgar Lobão, Jorge Linguiça

Schedules, Shifts, and Work Routines

The train whistle and the station siren long marked the lives of railway workers and residents. São João del-Rei is still known as the city of bells, which for many years dictated the passage of time here. With the arrival of the locomotive, timekeeping also became linked to time. Thus, knowing the train's departure and arrival times became part of the city's daily routine. The various daily trips took the steam locomotive to different parts of Minas Gerais: Barbacena, Barroso, Lavras, or Antônio Carlos. Workdays were long, lasting as long as needed to complete a journey that traveled through hills and rural landscapes. Railway workers spent long periods away from home, without seeing their families. As soon as they returned, they had to check their next departure time at the station.

"A schedule was posted here in São João del-Rei every afternoon. The scheduler, who was also the oldest engineer and a supervisor, would create the schedule and place it on the gate. The wall was perforated, allowing us to read the schedule from the street at night. If you arrived early, you could go inside to check it, or you might send a child to check it for you, asking, 'Go see where I’ll be tomorrow.' The schedule covered the entire day; trains would leave for any destination at times like 2:10 PM for Barroso or 2:10 AM for Aureliano Mourão."

Recouting by Luthero Castorino, retired train driver

"We would arrive an hour or an hour and a half early to prepare the locomotive for departure. This involved refueling with water, checking the oil or wood (during the wood-burning era), lubricating, and inspecting luggage. We would move the locomotive around the yard to ensure there were no loose parts and to listen to the sounds of the machine that had just come out of the shop. Then, we would wait at the station for departure. The same routine applied when returning from places like Aureliano Mourão or Antônio Carlos. Wherever we spent the night, we prepared the machine for 'sleep.' That’s why train drivers were so protective; it was like each locomotive belonged to its driver."

Recounting by Moacir Silveira, retired train driver

TRAIN DEPARTURE AND ARRIVAL TIMES IN 1898

Barbacena City Almanach, 1898. Robson Ferreira's personal collection.

Who Keeps Trains Running

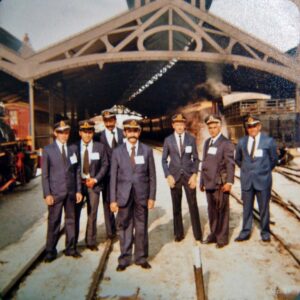

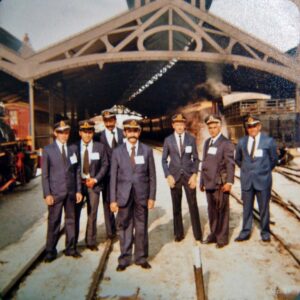

RAILWAYS WITH LOCOMOTIVE 68

From left to right: Sebastião Passos, Eli Batista de Araújo. Euler Cristóvão Resende, Mario Braga, Francisco Marques, José Roberto da Silva, Fernando da Silva, Edmar Viana.

Hugo Caramuru, date unknown. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS AT EFOM'S CENTENARY

Author unknown, 1981. ABPF NEOM Collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS IN THE SÃO JOÃO DEL REI YARD

From right to left: Ilair, Maurício, Flavio, Deoclecio, Walisson and Giovanni. Up on the locomotive: Alexandre Campos.

Author unknown, date unknown. Alexandre Campos’s personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS AT THE SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI WORKSHOP

From left to right: Mario Antônio Braga, Prudente Fonseca de Almeida, Sebastião Passos, Afonso Fernandes Rodrigues, Francisco Manuel Vieira (Baiano), Antônio de Castro (Mandi).

Back row: Manoel Eloi da Silva (Manoel Gradim), Osmar Mauro de Carvalho, Alfredo Martins, Antônio dos Reis, Jorge Vicentiniand Francisco Marques.

Author unknown, 80's. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

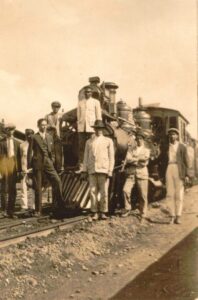

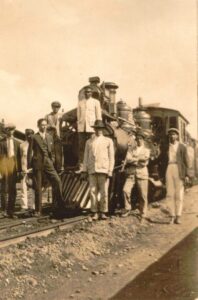

RAILWAY WORKERS WITH LOCOMOTIVE 217, CURRENTLY NUMBER 69, IN SÃO JOÃO

Author unknown, 1920s. ABPF NEOM Collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS WITH LOCOMOTIVE #1

Author unknown, May 1981. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

BENEDITO ALVIMAR AND EULER RESENDE AT THE SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI ROUNDHOUSE

Hugo Caramuru, date unknown. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS WITH LOCOMOTIVE 37 IN SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI

Author unknown, 1980s. Anderson Nascimento’s personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS WITH LOCOMOTIVE 22

From right to left: Bruna, Deoclécio, Flávio, Turista, Alexandre, Walisson and Giovanni.

Author unknown, May 24, 2009. Alexandre Campos’s personal collection.

RAILROAD WORKERS OVERHAULING LOCOMOTIVE 22

From left to right: Carlos Alberto, Gilberto, Leo, Baiano, C. Marques, Manola, Ivan, Zé Polvilho, Moacir.

Author unknown, 1981. Moacir Silveira’s personal collection.

RAILWAY WORKERS IN FRONT OF LOCOMOTIVE 21

From left to right: unidentified, unidentified, Roberto Caetano, Avelino, Waldir Lacerda, Nunes and Paiva.

Author unknown, date unknown. Solange Paiva's personal collection.

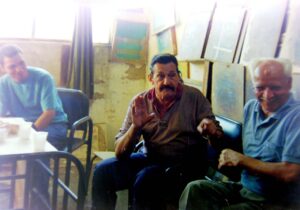

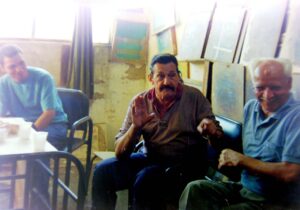

RAILWAY WORKERS TALKING

From left to right: Jonas Martins, Benito Mussolini and Sebastião Florêncio.

Hugo Caramuru, 2003-2004. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

RAILROAD WORKERS ON THE RAILROAD'S CENTENARY

Author unknown, 1981. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

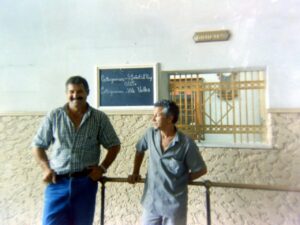

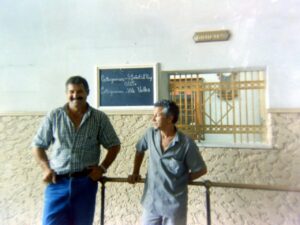

EDMAR MAZINHO AND EULER AT SÃO JOÃO DEL-REI STATION

Hugo Caramuru, date unknown. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

ADEMIR AND EDIMAR VIANA IN FRONT OF THE TICKET OFFICE

Hugo Caramuru, date unknown. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

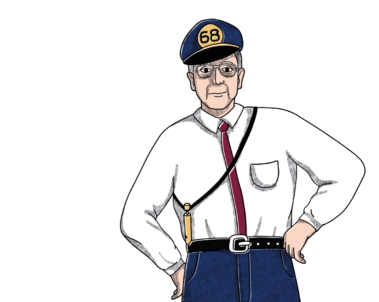

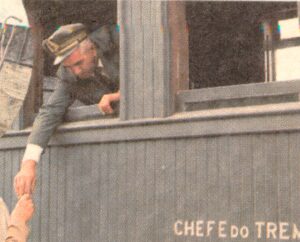

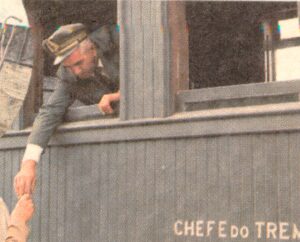

TRAIN MASTER, ANTÔNIO COELHO

Sergio Mártire, Ford Calendar, 1979. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

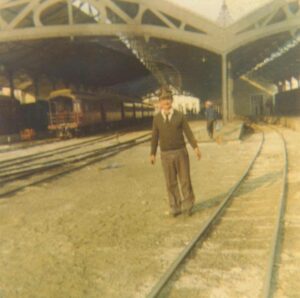

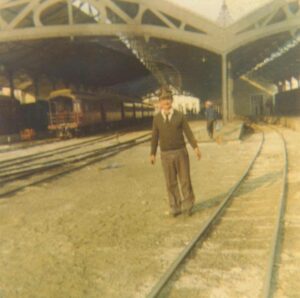

HEAD OF STATION, MR. OSWALDO

Author unknown, 1980s. Gustavo Zenquini's personal collection.

RAIL WORKERS WITH THE TRACK INSPECTION CAR

From right to left: Nilo Zampieri, Josmar Zampieri, Targino, Delvair Zampeieri and Celino. Hugo Caramuru, date unknown. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

RAIL WORKERS WITH THE TRACK INSPECTION CAR

From right to left: Zampierre, Targino, Mario Braga and Mazinho.

Hugo Caramuru, date unknown. Hugo Caramuru's personal collection.

Stories

Newspaper Scraps

I remember a story my parents loved to tell me. Once, we were traveling by train from Barbacena to São João del-Rei when it got derailed. It was already late, and the train would have to stay there overnight until the problem was solved. Dad told me he went from person to person asking, "Do you have a piece of newspaper to spare?", "Oh, I only have this little piece," some would reply. He collected the pieces and wrapped me in them. I was all bundled up in newspaper to keep warm. He worked in printing and used to say that this was the power of the newspaper, it also had the power to bring warmth. So, that night, me, him, and mom slept by the roadside, but I was the only one who didn't get cold.

Story provided by Maria Lúcia Monteiro Guimarães , retired teacher and local resident.

Watering the Machine

Once, an old-time railroad fireman went to work with another veteran railroad worker; both were quite methodical. It was common for train drivers to make a hand signal to stokers so that they would check the machine, to see if there was water in the boiler. That day, the train driver made a similar signal to the stoker, but he was actually asking him to make coffee for him. However, the stoker thought he was being asked to put water in the machine's injector. When the train stopped, the train driver asked, "What did you do? Didn't you see I asked for coffee?" And the stoker replied, "That signal you made means the machine needs water. Now, if you'd like some coffee, I'll gladly make it, but you'll need to ask for it respectfully!"

Story provided by Hugo Caramuru , retired, local resident.

Fino Congo, Cachaça, and Pork Cracklings

There was a guy at Congo Fino Station tasked with painting it. An engineer warned the painter, "Don't start drinking; just focus on your work, paint the station, and catch the last train." The painter responded, "No worries, mister, I won't drink." But at every station, there was cachaça and pork cracklings, so it was tough to resist. So, the painter ended up drinking and chatting all afternoon. A train driver got there and mentioned that the last train was about to leave. Then the painter replied: "Wait a minute, I'm going to paint here really quickly, because I have to get home today". He rushed, painted, and left on the train. The next day, the engineer called him in and said, "I told you not to drink, and you did it anyway." The painter replied, "What do you mean, mister? I did everything right!" The engineer said, "Then why does it say Fino Congo instead of Congo Fino? Go on the next train and fix it."

Story provided by Hugo Caramuru, retired, local resident

Looking for a Wagon

All the wagons were numbered, and there was always someone responsible for painting them. My father, Manoel Gradinha, worked as a railroad painter. One day, a wagon went missing. As it was a narrow-gauge wagon, it could have been anywhere from Aureliano Mourão at Km 102 to Antônio Carlos at Km 0. People searched everywhere, but it was nowhere to be found and nobody found it for a while. Whenever a train left, the head of station would list the engine number, the train driver's name, and the numbers of the wagons on a clipboard. These numbers indicated where each wagon was going and where it was supposed to be—it was a form of control. Then one day, the head of station was checking the clipboard and suddenly saw the same number twice. He had painted the same number on two wagons that were going around unnoticed.

Story provided by Adalmir José da Silva, painter and local resident

Congratulations, 68!

It was just me and a few friends when locomotive 68 turned 80. So, we bought a cake for her, to sing 'Happy Birthday' to the machine. After we sang, one friend joked, "Now we're going to eat the cake, right?" It was just an ordinary bakery cake. I opened the furnace door and threw the cake inside—it was her birthday, after all. If we wanted cake, we should have bought one for ourselves. The cake went into the machine, and people were mad at me.It was just me and a few friends when locomotive 68 turned 80. So, we bought a cake for her, to sing 'Happy Birthday' to the machine. After we sang, one friend joked, "Now we're going to eat the cake, right?" It was just an ordinary bakery cake. I opened the furnace door and threw the cake inside—it was her birthday, after all. If we wanted cake, we should have bought one for ourselves. The cake went into the machine, and people were mad at me.

Story provided by Alexandre Campos, traction inspector and train driver

Fish and Palm Thorn

We were on one of the last trains passing by a pond near Congo Fino during October, when the ponds were drying up. Suddenly, a colleague exclaimed, "Oh my!" and asked to stop the train. They applied the brakes and found lots of fish stranded in a drying pond! Everyone rushed down and caught lots of fish. At that moment, Nelson stepped on a palm thorn, laid by landowners to prevent people from fishing. The thorn went through his foot and came out the top. We rushed him to the car, as he screamed in pain. Luiz Gonzaga then said, "Let’s deal with this thorn right here." These thorns have barbs and usually require surgery to remove. "No worries, I’ve got this," he declared. He fetched a bottle of cachaça, poured a hefty glass, had Nelson drink it, and said, "Bite on this cloth!" Then he grabbed pliers, pulled the thorn upwards, and removed it. By the next day, Nelson was walking fine! I thought, "Who needs health insurance when you’ve got cachaça? Cachaça healed the man!" We enjoyed the fish all the way to Congo Fino station and ended up giving much away because we had so much and no fridge to store it. They set up a makeshift wire clothesline to dry the fish, turning them into something like salt cod. We played cards and ate fish during the whole trip.

Story provided by Moacir Silveira, retired train driver

Did You See a Train Go By?

Once, the locomotive started moving on its own here. When I was in charge, they had installed chocks on the locomotive to prevent this. If a steam pipe leaks, the locomotive can start moving on its own. This happened with locomotive No. 1 because it had issues. It was there just to provide steam to other locomotives, so it was always fired up. Some watchmen were on duty, overseeing the workshop yard. Then, one night, they left No. 1 pressurized, and it began moving on its own. By the time a watchman noticed, the train was already smashing through the gate and speeding away! The watchman ran out into the night, frantically asking if anyone had seen a train go by. The locomotive eventually stopped near Casa da Pedra, close to Tiradentes, when it ran out of steam. It had traveled a considerable distance because it still had substantial steam pressure. And there was the watchman, running behind it, still asking if anyone had seen a train passing by.

Story provided by Francisco Marques, retired mechanic supervisor